Thursday, April 16, 2020

Tuesday, March 17, 2020

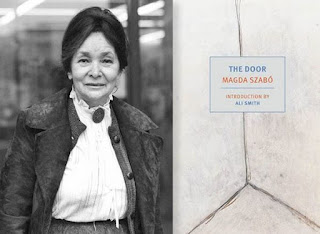

Comments on The Door by Magda Szabó

This is an odd book. It recounts the growth and end of an intense relationship between a wishy-washy writer and her traumatized and autocratic cleaning lady. It was was first published in Hungary in 1987 and arose in an atmosphere of intermittent but ever-present government oppression. Szabó, like the writer in the novel, endured a career fluctuating among prizes, forced appearances, and banned books -; on one occasion a prize and the book banned on the same day.

The cleaning lady, whose name is Emerence, is a fully drawn and haunting character. Her path to working for the writer began and continued in a series of traumas, such as her two siblings dying before her eyes as young adolescent and her traumatic self-sacrifice in presenting an abandoned Jewish baby to her conservative village as her own. Her life suggests the essential life of citizens under an arbitrary and autocratic regime.

In the book, the author slowly doles out knowledge of Emerence's traumatic past step by step as it is discovered by the writer, who fails to be inquisitive in the face of Emerence's perennial proud silence. Their relationship, as they finally acknowledge, is like mother and daughter and a model of autocratic parenting. At one point Emerence says that if someone is to love her, she must love her alone, although she tolerates the writer's husband, as he tolerates her. Finally Emerence's becomes ill and wants the world to allow her to die, which the writer at first prevents and then implements. Pages after Emerence's death provide a satisfying, adagio coda.

The prose suffices but is not striking.

Whereas the development of Emerence is full and vivid, the account of the writer is tenuous —: for example we don't know what she writes, nor do we know what if anything in her history allows her to submit to this relationship. A community of secondary characters is well drawn as far as they revolve around Emerence and are illuminated by her attitude toward them.

These unpleasant characters with an ugly, quasi-parental relationship limited my enjoyment of this novel but set me thinking of other works with similar situations that I like. What's the difference? Take St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose novels. Emerence is empathetic, selfless, and cuddly compared to protagonists parents. Yet I enjoy and respect the book. One reason is St. Aubyn’s page after page of exquisite prose. Another may be Patrick carves out a sort of mental health. I wondered if the tone of the part of The Door after Emerence’s death is somehow equivalent to Melrose' eventual recovery? In some way it allows us to recover.

Patrick has suffered from trauma and like many victims of trauma his bundle of self constantly threatens to disintegrate, whereas Emerence holds herself stiff and tight. In a long scene in the second novel when he is heavily laden with assorted drugs, Patrick's bundle of himself unravels into myriad voices rather like Leopold Bloom's trial in Ulysses and the issue of coherence of self continues through the books. Is Patrick's shaky self-cohesion more sympathetic for the reader than Emerence’s almost heroically stiff self-control?

Or take King Lear. Lear is an unpleasant character who has terrible relations with his children, but I love and admire the play. In the course of the play Lear changes his perspective on things. It seems integral to Emerence that she does not change her perspective; she would attack anyone who suggested she might. It is part of her holding herself together tightly. But what kind of book would we have she did?

Or Dorothy Sayers' Peter Whimsy mystery novels. Lord Peter comes from the same social world is Patrick Melrose and likewise suffers from a history of trauma, in his case from the First World War. His gentleman’s gentleman, Bunter, plays a role in most of the novels and stories, sometimes a dominant one. Of, Bunter, Whimsy's mother says, "It's that wonderful man of his who keeps him in order...so intelligent...a perfect autocrat." Yet the novels are engaging. Lord Peter is more attractive than the writer in The Door, the plotting is more intriguing, and Bunter has subtlety in how he controls Lord Peter. Maybe most important, Bunter has Whimsy's best interests at heart whereas Emerence is uncompromisingly self-centered.

Monday, July 29, 2019

Comments on Circe by Madeline Miller

Odysseus Vase Odysseus and the Sorceress Circe. Greek vase, c.700BC

We regularly see novels these days where someone grows up in a dysfunctional family, is the unpopular girl in high school, discovers a vocation that gives her confidence and identity, has some experiences with men, good and bad, which stretch her emotional range and boost both her apprehension and her confidence, finds the right guy, and settles down to a satisfying life. This is such a novel dressed up in Greek classic paraphernalia. In archetypal terms, it is the ugly duckling story grafted onto the little mermaid story.

Although incidents have plots, the main narrative is the story of her life. She is born as a minor goddess to another minor goddess married to the sun god, Helios. She lives in a family compound with related gods where she is considered less attractive and is not given much of chance for a good marriage. She discovers she can work magic based on herbs and her own powers and, among other things, turns a fisherman (Glaucos) she befriends into a god and turns her obnoxious older sister Scylla into a monster that lurks on a rock and eats passing sailors. For using magic, which is generally taboo to the gods, her father exiles her to a pleasant island. Several adventures involving love affairs with figures from Greek mythology mortal and immortal and her difficult relations with her sister and brother garnish her exile. Finally Odysseus arrives and stays for a year with her as stated in the Odyssey. But it is told from her point of view and she provides a lot of realistic details about what interests him and how his feelings run. In the end he goes on his adventures and she is pregnant. Alone on her island she has a difficult pregnancy and a hard time raising a child. As a young adult her son leaves to seek his father. He returns with his father’s wife, Penelope, and his half brother, Telemachus in tow. He recounts how he accidently killed Odysseus, then goes off to Italy to become a king; Circe turns her self into a mortal and forms a couple with Odysseus’ son by Penelope-; Penelope stays on the island.

The prose is smooth and clear if not exciting except for a sprinkling of poetic metaphors and phrases.

The characterization is mostly like the prose, effective but not exciting. In one respect it is particularly effective. That is its attention to how a few characters change over time. Time for the immortals differs from our time and it is a little vague. The period from her birth until Circe meets Odysseus is vaguely hundreds of years long. Of immortals, Circe alone changes. Miller constructs a convincing arc of character from an empathetic but petulant "teenager" to an enterprising and rebellious young adult, to a jaded thirty-something, to a harried mother, to a wise and capable woman. The progression of Odysseus is more of a crash, off stage, from arrogant hero to traumatized insecure monarch. The progress from infancy to young adulthood of their son is also carefully constructed and drawn.

But a changing Odysseus brings us to an issue about this novel.

Let me emphasize that I am no Greek scholar in pointing these matters. I don't read Greek, but I’ve read lots of translations and secondary sources and am a knowledgeable amature.

The novel departs from the body of Greek mythology in various ways. Note, there is no bible of Greek mythology. Instead, a variety of often-conflicting sources spread over centuries, so it is sometimes complicated or even ambiguous whether something is a departure. Miller seems to have mainly used three sources. First the Odyssey, usually considered to have been created around 800 BC. Second is the Theogony (The Genealogy of the Gods) from about the same time. The third is the Telegony (the story of Odysseus son by Circe, Telegonus) (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telegony). The text of the Telegony is lost but it survives as a summary, as an adaptation in Latin from the 1st century BC, and other fragmentary sources. Miller has evidently studied this Latin version. There are other fragmentary and late sources, for example Ovid's Metamorphosis written in Latin shortly before the end of the BC's, that is about 800 years after Homer in a very different culture.

Anachronisms: There are various minor anachronisms in the presentation. For example at one point Circe describes Odysseus as being like a lawyer. There were no lawyers in Greek mythology and, indeed, the society was without a judiciary apparatus.

Choices:Miller necessarily makes some choices about which versions of Greek legends she uses. One is about which God's to describe. Versions very, but roughly speaking Greek gods fall into three groups: the Olympians, Zeus and his siblings and their dysfunctional spouses and children; the Titans who are the siblings and relatives of Zeus's father; finally the Chthonic deities who are associated with the underworld and whose ceremonies were often at night (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chthonic).

In the Iliad, Homer limits himself to the Olympians and mainly so in the Odyssey. Miller recalls the war between the Titans and the Olympians, draws on their rivalry for motivation, but chooses to ignore the chthonic deities, which were important in the everyday life of Greek people. What is relevant here is that Circë is sometimes described as the child of Perse, a Titan ocean nymph, and sometimes described as the child of Hecatë a chthonic moon goddess, witch, and, like Legba, deity of crossroads. In either case her father is Helios a Titan sun god. It always seemed to make more sense to me that Circe should be descended from Hecatë because she is a witch and witchcraft is not a common trop in Greek mythology.

Another change is the story of Glaucos. In European literature the image of Glaucos comes mostly from the version in the Metamorphosis by Ovid. Other classical references are scattered and brief. Ovid describes Glaucos as an immortal who was accidentally turned into a God by exposure to a magical something or other. He then falls in love with the nymph Scylla who rejects him. He goes to Circe, a competent witch in Ovid's version, seeking a love potion, which leads to various ill consequences. Miller has changed the story. In her version a naïve Circe falls in love with the mortal Glaucos and turns him into a God because she wants him to live forever with her. As a sea God he falls in love with Scylla, not Circe, which leads to various ill consequences. Miller's treatment of Glaucos artfully presages her account of Circe's later love for Telemachus where she wisely, in Miller's view, resolves their difference in mortality by becoming mortal herself.

To take another significant choice, Odysseus’ death is not recounted in the Odyssey, but there is a clear prediction by the highly reputable seer Tiresias that he will die of peaceful old age. In the Telegony he is killed by Telegonus and Miller chooses that version.

Creations: Occasionally Miller makes up legends, at least as far as I understand them. For example, the origin of the poison spine that kills Odysseus. It is in the Telegony that he is killed with a spear tipped with a spine from a ray, but there is no story about Circe marching under sea to confront a ray god, there is no ray god.

Violations of the classic culture: The most important ways Miller departs from the spirit Greek mythology have to do with the importance for her of change. In Greek mythology there is no notion of gods changing. A god's stage in life is as immutable a characteristic as her domain of power, her sacred animal, her weapon, etc. A minor example occurs in a conversation between Circe and Glaucos (before his deification). They have been hanging out together. In the first place, in classical mythology gods and mortals don't hang out. They meet during dramatic or significant moments. The closest thing to hanging out is the relation between Athena and Odysseus in the Odyssey, but even there the goddess only shows up when Odysseus is particularly in need. Circe mentions in chatting that she met Prometheus. Then-mortal Glaucos is startled because Prometheus' crime and punishment occurred hundreds of years ago in time as he figures it.

"His eyes were fixed on me. 'But you are my age.' My face had tricked him. It looked as young as his."

But mortals in Greek mythological times, thought of gods as "ageless." That is, age did not pertain to them.

Less casual is her account of Odysseus as a figure of change. A central point in the Odyssey is that despite his adventures, misadventures, frequent deceit of others about himself, and frequent changes of appearance and body, implemented by Athena, from ragged, aged beggar to buff warrior, despite these things he remains essentially unchanged. This is unlike, say, Gilgamesh, the protagonist of the roughly contemporary near eastern epic, who through complex adventures and self-reflection accepts his mortality and becomes a better king. In the end, Miller crashes Odysseus into an frightened, desperate figure, something deeply contrary to Homer's image of the hero.

Another departure from the classical conception of immortals is Circë’s unhappy childhood and adolescence as the slighted girl/goddess. Gods may embody emotions, and frequently bicker like the members of a dysfunctional family, but these conflicts manifest in traumatic scenes like Hephaestus discovering his wife Aphrodite in bed with her brother Ares, but they lack protracted identity sieges. This is the stuff of current young adult novels, not Greek mythology.

So what? Miller has modified and departed from the letter and the spirit of her sources in various ways to implement a typical 21st century story. Why should that matter? The lengthy and thorough Wikipedia article on Circe documents how her story has been recounted and her image represented in disparate ways over the centuries. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circe). She may be a symbol of gluttony, of lustfulness, of the evils of witchcraft, as an embodiment of evil female wiles or a feminist figure as in Miller’s novel, etc. Her story maybe a homily against drunkenness or on occasion to question whether living without reason like a beast is better than being rationally human. It varies as the interest of individual times and writers demand. Why should we expect anything else in the 21st-century?

For me the issue lies in whether we 21st-century Americans want to regard ourselves, even enriching versions of our own preoccupations, or do we want to reach out for human culture and caring.

It is interesting to compare Circe with two other recent novels set in Greek mythic times. One is: The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker, which retells the quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon from the viewpoint of the captive slave girl whom they fought over. The gods are almost absent from Barker’s book, which is about mortals save for the sea nymph Thetis who is a background character shadowing Achilles. Barker's book sticks very close the events of the Iliad and makes us feel the emotions of an ordinary upper-class girl of those times responding with a modern psychology to the mostly terrible events she witnesses. Barker is searching the meaning of war by cross-fertilizing its ancient action with modern understanding of trauma.

Another is Colm Toibín's House of Names, which tells a story of Orestes’ vengeance on his mother. Toibín invents an entirely different story hardly related to the Orestes portrayed by Aeschylus in the Oresteia. Gods are present merely in the images and feelings that human characters have of them. He projects feelings and reactions of someone in Orestes position following a modern, dynamic psychology, and the events of the story develop from the difference between Toibín’s premises in the premises of a classic Greek. He makes us consider what it would mean, universally, in human culture, to kill your mother, by casting his made up story against the shadow of the mythic version.

Barker’s novel amplifies and Toibín’s novel almost abandons what is handed down from antiquity. Barker’s Brieseis and Toibín’s Orestes are no more like the corresponding classical figures than is the Circe in an 18thcentury French rationalism version. But they tell us something by reaching out of our own perspective.

Another interesting comparison is with Shakespeare’s Roman plays. Shakespeare followed closely his principal source, the Greek writer Plutarch, who worked shortly after the events in a time when Rome first dominated the Mediterranean politically and was itself much influenced by Greek culture. He was a keen observer of men and mores. He was a Greek diplomat and had lived in Rome, so he knew both cultures well. Shakespeare carefully preserves his perspective in many ways, for example in presenting the suicide of four central characters. For Christians of Shakespeare’s England suicide was a mortal sin, your soul went to hell, as Hamlet considers in his famous soliloquy. For Romans of the republican period it was an appropriate, indeed praiseworthy act in the event of catastrophic defeat and when we watch those scenes, the perspective has passed from Plutarch, through a translator, to Shakespeare, to us. Consider the scenes in which Brutus and others fall upon their swords, and also the scenes when other characters like Anthony react to the news. Consider Anthony’s praise for Brutus against his own later suicide. Here we feel deeply what character means in other cultures. It is this meaningfulness that the novel Circe fails to provide.

Wednesday, January 9, 2019

Comments on the 2018 Kaua'i Writers Conference

From November 5th - 11th I attended the Kaua'i Writers Conference

(http://kauaiwritersconference.com). It had two aspects, first four days of

master classes, and then three days of the conference more broadly.

Kaua'i (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kauai) is a genuine

tropical paradise, a relatively small Hawaiian island with a population of

about 60,000. It happens my son teaches high school there, which is one reason

I attended. The picture is one I took of

closing ceremonies on the beech.

The master classes seemed to have up to about 30 students each

and met for three hours a day with one or sometimes two teachers. (https://kauaiwritersconference.com/master-classes/)

In the conference there were a variety of talks on various aspects of writing

and publication. (https://kauaiwritersconference.com/schedule/)

It took place in a grandiose, slightly worn resort with the

largest swinging pool in Hawaii half-ringed with hot tubs and an island in the

middle. All overlooked a beach on an

inlet. (https://www.marriott.com/hotels/travel/lihhi-kauai-marriott-resort/) Our

room was nice but not fancy, the food was good by conference standards. Things generally

ran smoothly.

Demographics: My perspective may have limited my count, but I'd

guess there were about 200 people in Master classes and about 300 attendees to

the conference as a whole. There was a range of age and nationality, but the prominent

group was middle-aged Caucasian women. My impression was that about half of the

attendees were from the Hawaiian Islands. There were a scattering of Asians and two

blacks (one from Nigeria). A few places had

been allocated to students from a local college. I was sitting for lunch one

day with a Brit. Conversation turned to how people stood in

line for busses in different cultures. (I. E. a lone Brit is visibly in a queue

whereas in Greece any group is a mob.) A young Asian woman sitting next to me

had been rather quiet, so I asked her where she was from. She said Saipan; she was

one of the local college group. I asked about bus queues. She said there are no

busses in Saipan.

My impression was that the most popular genre was memoirs by

people who believed they had led interesting lives or, more often, had had

interesting jobs or professions.

I attended the master class given by Nicholas Delbanco (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Delbanco)

on voice. It had some virtues and some faults. The faults were size and the

room. Some fell away, but at the beginning there were 30 people. The room,

which could have held 60 people, had narrow tables arranged in ranks as for

hearing a lecture; it should have been is some sort of round-table arraignment.

The virtues were the writers and the teacher. There were too many of them, but

the writers were almost universally smart, experienced, and serious. Typically

they were people who had written in some other field (I.e. the author of

several history books, a lawyer who had written books on law etc.) and now

wanted to write fiction.

Delbanco has immense experience

and resources as a teacher of contemporary writing and did marvelously considering

the number of participants and the inappropriate room.

The version of the conference I

attended two years ago (http://thothbooks.blogspot.com/2016/11/notes-on-kauai-writers-conference.html)

was dominated by people form the traditional publishing world to the degree

that, with a couple of exceptions in panels, it was as if hardcover books were

the only game going on in publication, a strange illusion. In 2018 that was no longer the case. Talks

included discussion of electronic publishing, self-publishing, how to

manipulate Amazon, and something new to me, "hybrid publishing", a

sort of cross between self and traditional publishing, where a publisher

selects a book submitted by an agent or author and they then share the cost and

allocate any profits in varying proportions depending on what each contributed.

Never the less agents and prominent

writers set a lot of the tone.

Characteristically the prominent writers urged people in the audience to

be true to themselves, write what they inwardly wanted and the like, whereas

the agents delivered strong guidelines about what the publishing industry wants

and expects. Jayne Smiley, who always intended to and does write different

sorts of books, commented that winning the Pulitzer Prize helped in arguing with

her publisher. Her agent, however, told a story that elicited some sympathy for

publishers. There used to be a mystery writer named Sue Grafton who wrote a

series of rigidly similar mystery novels. Her publisher wanted her to write

them as fast as twice a year whereas she wanted to slow down to one every two

years, or something like that. The agent pointed out that at that time Grafton’s

novels accounted for about half the publisher's income.

A couple of writers who had a calling

to speak for their minority group were prominent in the conference two years

ago and that was a live topic of discussion. Not this time.

Of the many talks (https://kauaiwritersconference.com/schedule/)

the one I attended and enjoyed most was Smiley. I've read only one of her books

(A Thousand Acres) and was only moderately impressed, but she's fun and smart

and has had an interesting career. The

one I liked least was billed as on the Jungian notion of the hero’s journey. I

thought, good, I can get ideas about plot structure. It turns out she was

interested in only on step, (the second, "Refusing the Call"). She

gave us brief writing assignments related to evocative phrases. One was

"The stakes were high." Feeling irritable, I wrote about an enclosure

walled by stakes so high they made the garden shady.

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

The Demo at 50

I spent Sunday at a symposium on the

50th anniversary of a demo of the Online System (NLS) by Doug Engelbart and his

group in 1968. The demo is famous in computer history.

I joined the group in 1970, about two years

after the demo and stayed till 1980. The first two talks in

the morning were about the demo and how it had been achieved. Computer processing necessary for the demo took

place at SRI in Menlo Park and was connected to Engelbart controlling the

computer and dwarfed by a giant display screen in what is now Bill Graham Civic Auditorium by a

two-step microwave link. The whole

process was intricate, fragile and something of a miracle in terms of both

software and hardware. Of course, I'd

heard about it, but never in such detail with excellent slides created by some

of the people who did the work. I found

the morning very interesting.

By my guesstimate there were about 250

people gathered at the Computer Museum in Mountain View,

roughly one tenth of the people who saw the demo. The audience was dominated by old, white men,

as were the presenters. About half of it

was younger, down to teenagers, but again predominantly white men.

Engelbart's work is conceptually separate

from the Internet, but historically it has been much entwined with it. His lab at SRI was the second node on what

became the ARPANET and eventually the Internet.

The notion of linking documents came from Doug and/or a philosopher

named Ted Nelson (see below), but the implementation, as we know it in the

Internet today, came later from other sources.

All of the speakers credited Doug's person

and his thinking as important influences in their lives.

Later morning sessions discussed the immediate

impact of the demo on computer research and development.

The sixteen presenters, including several

computer luminaries, expressed many interests and viewpoints, but the afternoon

sessions tended to focus on whether Engelbart "vision" was being

fulfilled by the contemporary computer world.

Engelbart set out his vision in a paper in 1962. Basically it is not a vision about hardware or software, but about building

tools to aid the process of solving problems: "By

"augmenting human intellect" we mean increasing the capability of a

man to approach a complex problem situation, to gain comprehension to suit his

particular needs, and to derive solutions to problems." Speakers were in

general highly aware of the distinction.

Speakers tended to say that the computer

world has sadly failed to implement the vision, mostly because it has been

diverted into getting rich. There was

some criticism, for instance of Google, even though Google was one of several

sponsors of the meeting. One speaker recalled

the first time an advertisement appeared on the Internet and his moral disgust

at seeing it there, which was shared by his colleagues. Facebook took several hits from speakers,

although I notice more than one person sitting in the audience sneaking a look

as they listened. Wikipedia was several

times praised. This was a group of

smart, collegial, bland, and well-off guys, and a few gals, beating themselves

up for not having done more for the world in the manner Doug envisioned and

suggesting ways, none of them very likely in my perspective, of doing better.

In the foyer of the auditorium, there were demos

of software influenced by Doug’s thought or practice. Dean Meyers showed a version of NLS running

on Windows. I was most impressed by a

small teaching tool based on links running on an Apple II. It's been a while since I saw a running Apple

II.

The problem from my perspective is that

forces like capitalism and the human propensity to divide into groups and

squabble tend to subsume whether people communicate with the aid of

computers. For instance, climate change

was mentioned several times.

Undoubtedly, computer-based exchange and examination of knowledge can

help with scientific and technical problems having to do with climate

change. But the coal companies have

computers too. At a high level,

everybody knows what to do about climate change: eliminate fossil fuels

and cultivate forests and other absorbers of greenhouse gases. This is not a technical problem -; it is a political problem. Again, Internet computer communication has

had diverse and profound effects on politics; whether they have reduced

conflict or mismanagement remains to be seen.

The methodical use of the Internet by the Russians and others to confuse

people was not motioned in my hearing and efforts by China to mold social identity was

mentioned only once.

The overall moderator was Paul Saffo who describes his occupation as "futurist." That and chatting with

old friends and acquaintances, some of whom I would not have recognized without

nametags, recalled to me how strange it was when I first began working in what

is now called Silicon Valley that people's identity seem to center on what they

hoped or planned to do rather than what they had done or where they had come

from. I have not yet become comfortable

with it. After all, the past has

happened and shaped us as it has. The

future is at best a plan and for sure uncertain.

The last speaker was Ted Nelson. He is extraordinarily eloquent. He described his personal and intellectual

relationship with Doug over a lifetime. I

cannot describe what he said, only admire it.

Tuesday, July 3, 2018

Fake News from the Rhine

Last week I attended the San Francisco Opera's production of Wagner's four operas The Ring of the Nibelungen. Let me first of all say that this was a satisfactory experience. The orchestra, central to these operas, was in great shape and wonderfully conducted. The singers were all good, some terrific. I could make some carping criticisms of some singers – there always such criticisms to make – but I don't want to bother. The acting was good. Above all, the special imaginative and emotional hit The Ring offers was present in abundance.

What is the special Ring hit? It is the musical re-evocation of themes, events, and objects, that have occurred through musical cross-references by means of repeated, sometimes altered but recognizable, Leitmotifs. Let me take a small example. When the most important female protagonist, Brunhilda, is a demigoddess riding high, the celebrated Ho-jo-to-homusic is associated with her entrance. At the end of the next Opera she has been demoted to mortal and obliged to marry the tenor. Basically she is happy with her fate —; she loves the guy and loves feeling love. But, realistically, her response is complicated and ambivalent. As she is exploring her ambivalence she recalls, (in translation) "Once heroes bowed to me.” When she sings those words we get a brief poignant touch of Ho-jo-to-homusic in the midst of her love music. Repeat that process 200 times and one hundredfold and you get a musical experience that enters your mind and emotions as no other. It is the result of intense and creative coordination of text, music, and setting.

But mostly I want to bitch about the stage setting. It's really awful, more awful than merely ugly or crude would be. Generally, it is not coordinated. Let me acknowledge first that in general I am uncomfortable with resetting plays or operas in times other than the author's intent, although it certainly can work. Let me acknowledge also that anyone presenting The Ring has a problem about setting. When and where does The Ring take place? It takes place in mythic never never land. And what pray does mythic never never land look like? Though Wagner provided ample descriptions of scenes in his libretti, the history of productions of The Ring is strewn with failures of staging. But we can be sure of a couple of things. It is set in the forest. The vast forest that covered Germany in the middle Ages as Wagner imagined it. Second it is set by, on, and in the river Rhine.

Wagner's idea of nature is not problematic. It is the solid and meaningful background in which the decline of the gods and triumph of human love takes place in The Ring. The notion that nature is something humankind is destroying by exploitation is a late 20th century idea at least in its popular form, well after Wagner.

The first scene of the first opera, Das Rheingold, challenges stage designers. Wagner’s detailed directions describe it:

(Greenish twilight, lighter above, darker below.

At the bottom of the Rhine

The upper part of the scene is filled with moving

water, which restlessly streams from right to left.

Toward the bottom, the waters resolve themselves

into a fine mist, so that the space, to a man’s height

from the stage, seems free from the water, which

floats like a train of clouds over the gloomy depths.

Everywhere are steep points of rock jutting up from

the depths and enclosing the whole stage; all the

ground is broken up into a wild confusion of jagged

pieces, so that there is no level place, while on all

sides darkness indicates other deeper fissures.)

(The curtain rises. Waters in motion. Woglinde

circles with graceful swimming motions around the

central rock.)

For reasons unknowable to Wagner, the stage director, Francesca Zambellohas decided to begin The Ring in California in the time of the gold rush, extend its duration to approximately the present, and through sets and projections depict the loss of the natural world to industrialization. In Wagner's libretto the action takes around 25 years and involves no reference to what may be going on outside the world of the story.

Of course the Rhine does not flow in California so, although the name of the opera is Das Rheingold and the Rhine maidens ("Rheintöchterin German) sing the German text, "Rheingold" etc., the subtitles read "River maid" and "River gold.” The river is a stream running through the middle of the stage and the Rhine maidens are not water sprits, but healthy looking California girls dressed in 19th-century party ware.

The powerful Sacramento River flows through California, was the location of the gold rush, and was involved in environmentally destructive placer mining, which appears on some screen projections, but Zambello ignores that. Perhaps the notion of subtitles translating Rheingold as “Sacramento Gold” was too ridiculous even for her.

At this point the staging is merely silly and distracting. It gets worse in the beginning of the third opera because it tampers with protagonist’s conception of self.

Wagner’s stage directions for Siegfried act I scene 1 are:

(A rocky cavern in a forest containing a naturally

formed smith’s forge with large bellows.

In this forest a villain named Mime has raised the ultimate hero Siegfried without exposure to other human beings. But he has been exposed to the forest. He constantly refers in dialogue to how he had learned about life and himself from the birds, animals, and trees of the forest and at one point leads in a bear, this arrogant adolescent’s idea of a joke on Mime.

But trees and rocks not what we see when the curtain rises in this production. Mime's cave has become a dilapidated mobile home located in an industrial wasteland (see above). No home for bears here. The real problem with this is that the hero could not have grown up with the self-image or the image of how to relate to others he had in an industrial wasteland. The scene leaves the audience possibly annoyed but certainly confused.

By the end of the opera via staging and projections the setting has progressed to a 20th-century industrial wasteland, which serves to suggest, nay assert, the destruction of nature by humans. Whatever the name of the river, it has dried up and we last saw the whatever maidens collecting garbage on its dry floor in a scene Wagner describes as set "in a remote wooded valley where the Rhine flows".

Between scenes toward the beginning of the last opera a substantial orchestral passage embodies musically the hero’s trip down the Rhine. The swelling music movingly reflects the flow of the river. It is frequently excerpted and has become a warhorse of symphony concerts. The curtain raiser for the first opera is a beautiful and hypnotic projection depicting a powerful river and related stuff. It would have been appropriate and satisfying to repeat it here. But no, we get more projections of industrial waste. It is weird to hear Siegfried’s Rhine Journey while looking at in concrete and power lines.

Wagner provides detailed stage directions for the end of the opera:

(As the whole space of the stage seems filled withfire, the glow suddenly subsides, so that only a cloud

of smoke remains, which is drawn to the background

and there lies on the horizon as a dark bank of cloud.

At the same time the Rhine overflows its banks in a

mighty flood which rolls over the fire. On the waves

the three Rhine daughters swim forward and now

appear on the place of the fire.)

(Hagen, who since the incident of the ring observed

Brünnhilde’s behavior with growing

anxiety, is seized with great alarm at the appearance

of the Rhine daughters. He hastily throws spear,

shield and helmet from him and rushes, as if mad,

into the flood.)

(Woglinde and Wellgunde [Rhine maidens] embrace his neck with

their arms and draw him with them into the depths

as they swim away. Flosshilde, swimming in front of

the others toward the back, holds up the regained

ring joyously.)

(Through the bank of clouds which lie on the

horizon a red glow breaks forth with increasing

brightness. Illumined by this light, the three Rhine

daughters are seen, swimming in circles, merrily play-

ing with the ring on the calmer waters of the Rhine,

which has gradually returned to its natural bed.)

(From the ruins of the fallen hall, the men and

women, in the greatest agitation, look on the

growing firelight in the heavens. As this at length

glows with the greatest brightness, the interior of

Walhall is seen, in which the gods and heroes sit

assembled, as in Waltraute’s description in the first

act.)

(Bright flames appear to seize on the hall of the

gods. As the gods become entirely hidden by the

flames, the curtain falls.

None of this happens as described in this production. Instead see a barren, post-industrial landscape. The Rhine Maidens, once flirtatious hotties, embodiments of positive libido, are now bedraggled and bent. Siegfried is not on a pyre of wood for Zambellohas moved his immolation off stage, but Gibichung vassalsn are carrying old tire casings in that general direction. Valhalla is not seen. Etc. Most important the Rhine does not flood the stage. There is no Rhine, and whatever river flowed in the first opera has dried up.

Because the Rhine does not reflood the stage to allow the Rhine Maidens to swim up and remove the ring from Siegfried’s finger, the setting fails the resolution the text and music embodies. Zambello has imposed a moral of painful disharmony rather than resolution. She ties to solve the problem she has created by adding a child who comes on stage after theverything Wagner wrote is over carrying a sapling, which she plants. This is Bullshit. This is Fake News. And like political fake news, the confusion it causes is as bad as it's dishonesty.

The libretti Translations are by Frederick Jameson .You can read them all at: http://home.earthlink.net/~markdlew/shw/Ring.htm

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)